For the first post on this blog, I figured a brief history on the phrase “À la lanterne!” made the most sense. Before Madame Guillotine became the revolutionary weapon of choice, the angry mobs of Paris turned to the lamppost for justice.

Before the French Revolution, France was divided into three estates, or classes. The First Estate consisted of the clergy. The Second Estate consisted of the nobility. The Third Estate, approximately 98% of the population, consisted of everyone else. All three estates existed under the rule of the king, a monarch with absolute power. The First and Second Estates were exempt from taxes, leaving an incredible burden on the significantly less wealthy Third Estate.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the terrible financial and economic crisis of the 1780s affected the Third Estate far more than the others. Food scarcity and cost instability meant many families were literally starving. As the suffering of the Third Estate grew, their resentment towards the clergy, nobility, and king reached a boiling point. On July 11, 1789 Jacques Necker, finance minister to Louis XVI, was dismissed. Necker was a reformist and loved by the Third Estate. His dismissal caused such outrage that it led to the storming of the Bastille on July 14.

Necker’s replacement was Joseph Foullon de Doué, a royalist handpicked by the King. Foullon is rumored to have mocked those suffering from famine: “If those rascals have no bread, then let them eat hay”. On July 22, Foullon was captured by a mob of enraged Parisians and dragged to the Hôtel de Ville. There, they forced him to walk around barefoot with a bundle of hay tied to his back. They then attempted to hang him from the lamppost, however the rope broke three times. Instead, they beheaded him, stuffed his mouth with hay, and paraded his head through the streets.

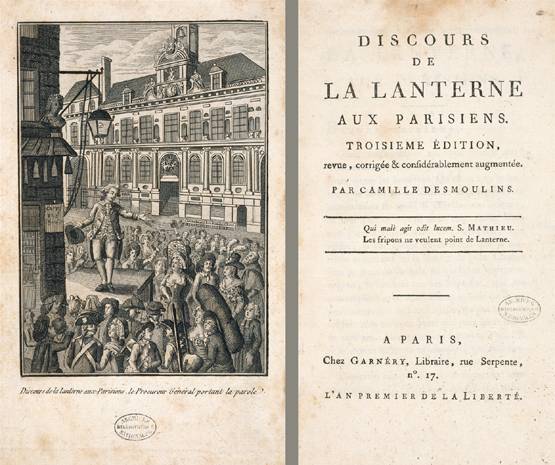

Foullon was the first prominent victim of mob justice à la lanterne (to the lamppost). He was not the last. In August 1789, Camille Desmoulins wrote Discours de la lanterne aux Parisiens (the lamppost speaks to Parisians) in defense of these lynchings. In turn, he became known as Procureur-général de la lanterne (Attorney-General of the Lamp-post). A popular song during the revolution Ça Ira contains the line “les aristocrates à la lanterne!”. The lamppost would continue as the revolution’s weapon of choice until being replaced by the guillotine in 1793.

The Historical Lesson

The phrase “À la lanterne!” is many things. It is a cry for justice, as well as revenge. It is a cry for equality, but also of hate. The horrible mob violence of the early French Revolution was a result of a people downtrodden for far too long. Forced to bear all the weight of a crumbling France, the Third Estate sought justice. Justice, however, was impossible under the current system so they enacted their own form of it, one consisting of blood and terror. They then tore down the system and everything associated with it: the clergy, the nobility, and the king. When justice seems impossible, revolution occurs.

I have named this blog À La Lanterne not because I celebrate mob justice, but because I believe it serves a lesson. Humanity desires justice above all, and by extension, liberty and equality. When the laws themselves are unjust, the oppressed will embrace the illegal. When the system in place encourages inequality, the unequal respond by destroying the system. To avoid revolution there must be hope of reform. If reform is impossible, then tyranny has taken hold, and the people rise up and cry “á la lanterne!”.

Sources

- Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette by Mike Duncan

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/À_la_lanterne

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Foullon_de_Dou

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camille_Desmoulins

Leave a Reply